4 min read

Cassini Camera Visualizes the Invisible During Jupiter Flyby

January 23, 2001

Cassini's recent pictures of Jupiter are providing scientists with

never-before-seen images of the giant planet's magnetosphere and underlying

dynamics.

For higher resolution image, click here.

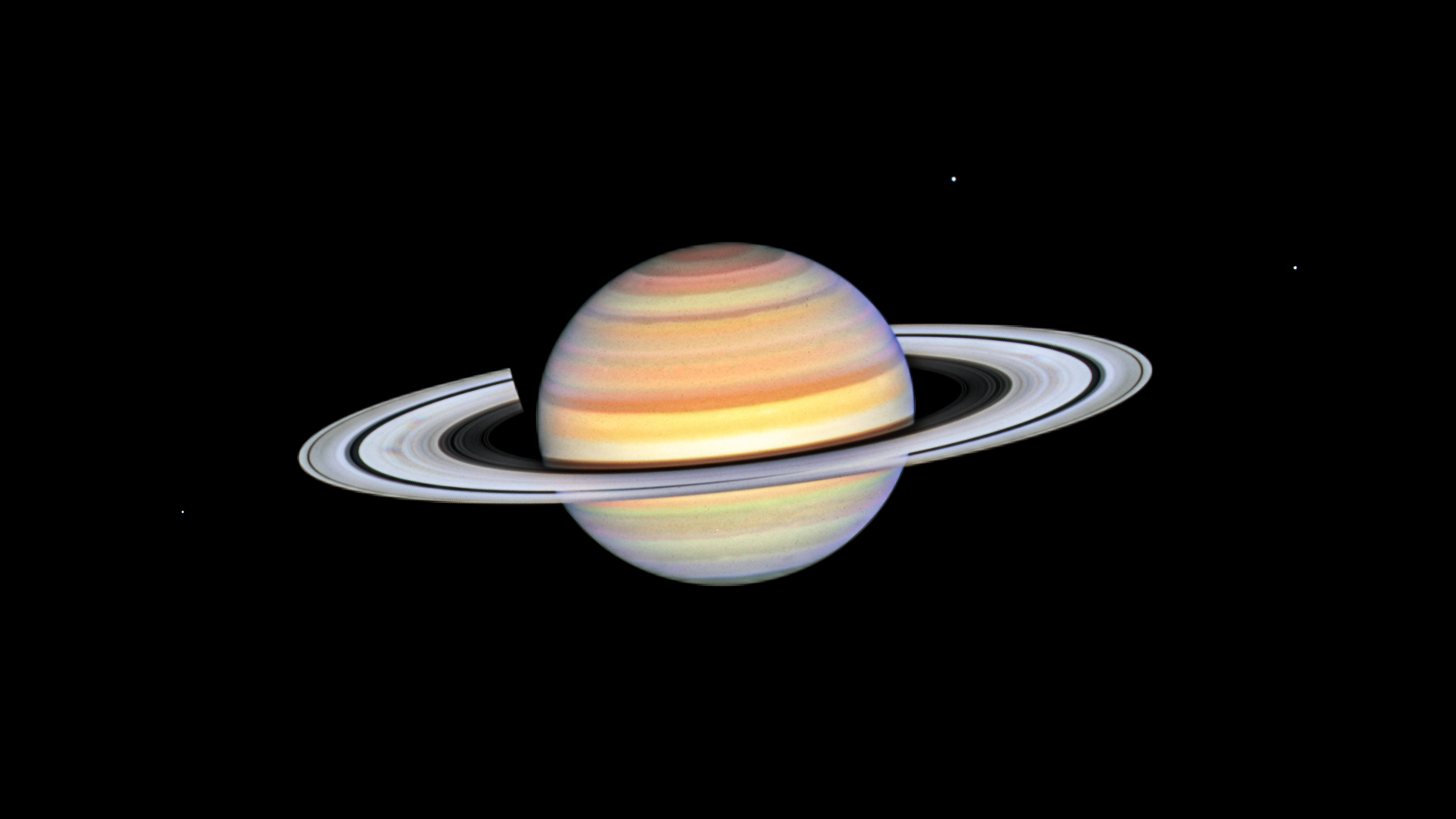

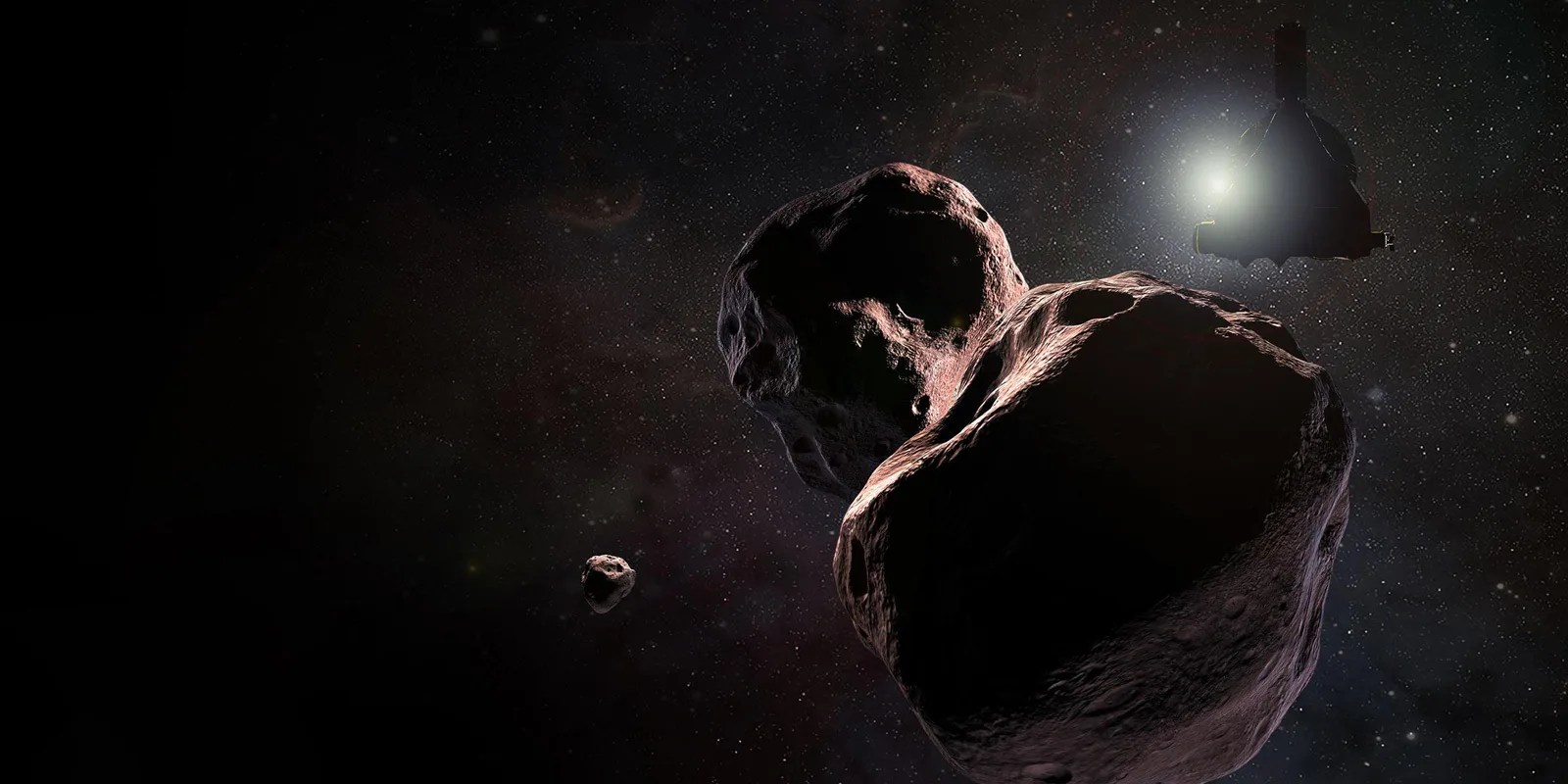

NASA's $3.4 billion Cassini spacecraft is presently in a six-month flyby of

Jupiter during a gravity-assisted swing toward Saturn and a four-year study

of the ringed planet that will begin in July 2004. Researchers using the flyby

as an opportunity to try out some of Cassini's advanced instrumentation are

reaping scientific rewards.

"Every new spacecraft carries instruments that expand our ability to see things," says

Dr. Stamatios Krimigis, Space Department Head at The Johns Hopkins University Applied

Physics Laboratory (APL) in Laurel, Md., and principal investigator for the Magnetospheric

Imaging Instrument (MIMI) aboard Cassini. "With MIMI, we're able to visualize the

invisible."

The MIMI instrument includes an Ion and Neutral Camera developed by APL, a spectrometer

built by the University of Maryland under Dr. Douglas Hamilton, and a high energy

particle detector developed by Dr. Stefano Livi of APL and a number of co-investigator

institutions. "By detecting various energetic particles and discriminating among them

according to energy and mass, the camera is able to obtain remote images of the global

distribution of these particles," says Dr. Donald Mitchell of APL, who leads the camera

science team.

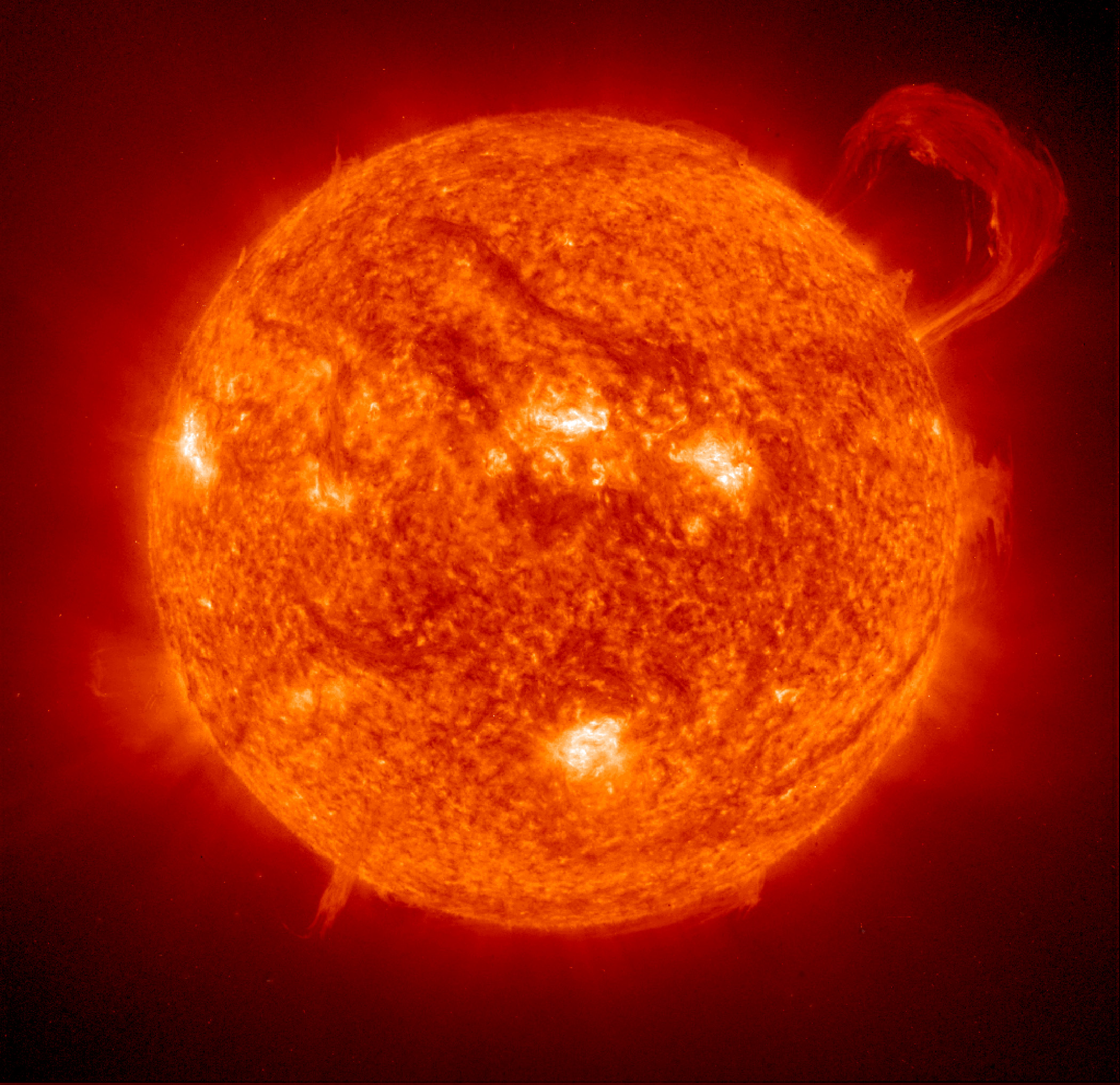

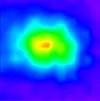

From a distance of 6 million miles (9.7 million kilometers), MIMI's camera has recorded

pictures of Jupiter's energetic particle-filled magnetosphere. Sequenced into a movie,

these images will eventually provide a large-scale look at the compression and expansion

of magnetospheres as they are buffeted by solar winds.

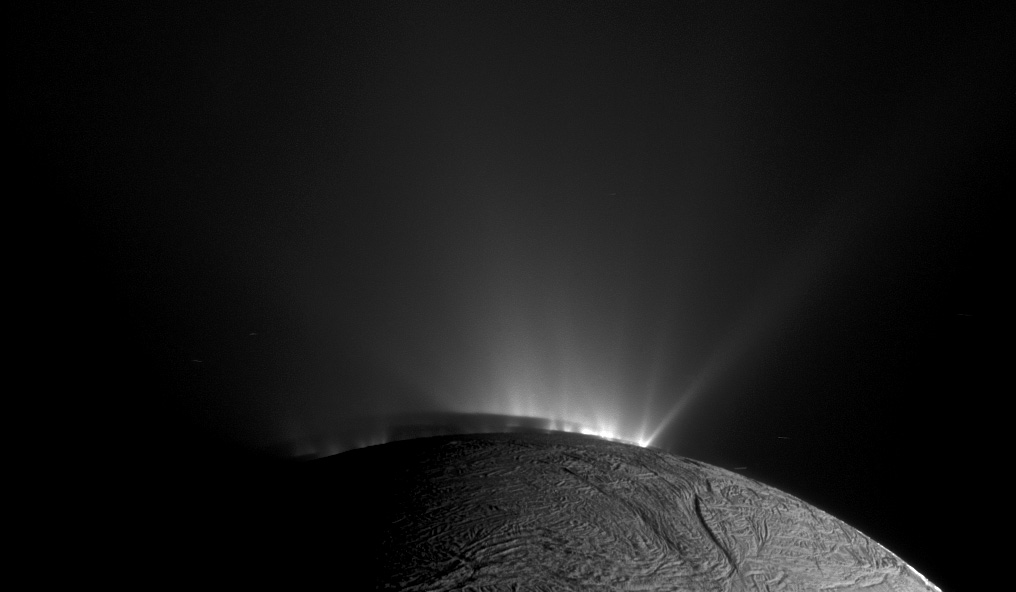

"These images, when combined with the other MIMI measurements, demonstrate the

ability of the camera to capture not only the shape and dynamics of the magnetosphere

but also elements of its chemical composition," says Krimigis. "They reveal that the

particles we're detecting - primarily hydrogen, but also oxygen, sulfur and sulfur

dioxide - are spewed from volcanoes on the Jovian moon Io and spun out into Jupiter's

magnetosphere, where they are trapped, energized and accelerated to high velocities.

Then, when collisions with other particles provide them with an electron, they become

neutral and are able to escape the magnetosphere. And that's when we can detect them

with our camera."

In addition to imaging the Jovian magnetosphere, MIMI's instruments have also detected

the presence of a huge nebula of particles enveloping Jupiter and extending out to at

least 13 million miles (22 million kilometers) from the planet, according to Hamilton,

the developer of another MIMI sensor that detected oxygen, sodium, sulfur, potassium

and sulfur dioxide. "All of these are constituents of the gas spewed out by Io's

volcanoes, thrown out of Jupiter's magnetosphere and eventually picked up by the flowing

solar wind," says Hamilton. Other observations include detection of flowing electrons

along the planetary magnetic field inside Jupiter's magnetosphere, according to Livi,

who developed the magnetic spectrometer sensor.

Closer to home, MIMI technology - in the form of a High Energy Neutral Analyzer (HENA)

instrument - is orbiting Earth in NASA's Imager for Magnetospheric to Aurora Global

Exploration (IMAGE) satellite, launched in March 2000. IMAGE obtained the first global

image of the Earth's magnetosphere, the shell of positively charged ions and negatively

charged electrons that lies atop our atmosphere and extends far out into space, says

Mitchell.

"By improving our ability to visualize a planet's magnetosphere - whether here or at

other planets of the solar system - we are better equipped to monitor its space weather,"

says Krimigis. "This will benefit science and, in the case of Earth, may lead to space

weather forecasts that will give advance warning of electromagnetic storms, which in

the past have disrupted communications and crippled electrical power grids."

For information on APL's MIMI instrument, go to:

http://sd-www.jhuapl.edu/Programs/program.php?id=5

Media Contact:

Ben Walker

Phone: (240) 228-6792

Ben.Walker@jhuapl.edu

Technical Contacts:

Doug Hamilton

(301) 405-6207

Stefano Livi

(240) 228-8413

Donald Mitchell

(240) 228-5981

Additional information about Cassini-Huygens is online at http://saturn.jpl.nasa.gov.

Cassini passed its closest to Jupiter on Dec. 30, 2000, en route to reach its primary destination, Saturn, in 2004. Cassini is a cooperative project of NASA, the European Space Agency and the Italian Space Agency. JPL manages the Cassini and Galileo missions for NASA¿s Office of Space Science, Washington, D.C. JPL is a division of the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena.

Media Relations Office

Jet Propulsion Laboratory

California Institute of Technology

National Aeronautics and Space Administration

Pasadena, Calif. 91109.

Telephone (818) 354-5011